In my previous article entitled “An Arbitration Mystery and Bulgaria’s Rule of Law: How Arnold & Porter Gave Away the Existence of a Secret Deal”, which I published on 11 August 2019, I explained how Arnold & Porter unwittingly disclosed that Bulgaria and the State General Reserve Fund Oman (SGRF) secretly settled their dispute before the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) over Corporate Commercial Bank (Case No. ARB/15/43). I also underlined that there would be more clarity about what happened behind the curtain after we learned on what grounds ICSID declared the case “concluded”. On 13 August 2019, the arbitral tribunal rendered its Award and the case was indeed marked as concluded.

Shortly after, Bulgaria’s corrupt government engaged in yet another mass disinformation campaign in which it claimed it won the case. However, the full procedural details of the case as published on ICSID’s website, coupled with Arnold & Porter’s statement about the case, prove that the parties settled and just asked the arbitral tribunal to record their settlement as an Award and rule on costs.

The Bulgarian government relies on the fact that an average person does not have a background in international arbitration, and Investor-State arbitration in particular. Luckily, not only ICSID itself has made a move towards better transparency by making the procedural history of each case public, but also many scholars have delved into ICSID’s case law and practice and have shed light on the application of ICSID’s procedural rules. This article may get technical, but if you are curious about this case, bear with me.

ICSID’s Procedural Rules and Practice

In my previous article entitled “An Arbitration Mystery and Bulgaria’s Rule of Law: How Arnold & Porter Gave Away the Existence of a Secret Deal”, I emphasized that Arnold & Porter’s statement about SGRF v Bulgaria is an example of a half-truth (Figure 1). They said that the claimant, the State General Reserve Fund Oman (SGRF), withdrew all claims with prejudice and that they only awaited a decision on the apportionment of costs by the arbitral tribunal.

In the same article, I also explained that under ICSID arbitration rules, a party cannot withdraw its claims. Rule 44 allows a party to discontinue proceedings:

Rule 44

Discontinuance at Request of a Party

If a party requests the discontinuance of the proceeding, the Tribunal,

or the Secretary-General if the Tribunal has not yet been constituted,

shall in an order fix a time limit within which the other party may

state whether it opposes the discontinuance. If no objection is made in

writing within the time limit, the other party shall be deemed to have

acquiesced in the discontinuance and the Tribunal, or if appropriate

the Secretary-General, shall in an order take note of the discontinuance

of the proceeding. If objection is made, the proceeding shall continue.

“Such an order will not normally contain a decision on costs. Rather, the parties must settle between themselves the apportionment of the costs incurred prior to the discontinuance.”

Under Rule 43, both parties can ask the arbitral tribunal to discontinue the proceedings:

Rule 43

Settlement and Discontinuance

(1) If, before the award is rendered, the parties agree on a settlement

of the dispute or otherwise to discontinue the proceeding, the Tribunal,

or the Secretary-General if the Tribunal has not yet been

constituted, shall, at their written request, in an order take note of the

discontinuance of the proceeding.

(2) If the parties file with the Secretary-General the full and signed

text of their settlement and in writing request the Tribunal to embody

such settlement in an award, the Tribunal may record the settlement in

the form of its award.

In this case, there are two options – parties can ask the arbitral tribunal to issue a Procedural Order for discontinuance or to record their settlement as an Award pursuant to Rule 43(2). If parties invoke Rule 43(2), they can either agree on cost apportionment themselves or ask the arbitral tribunal to rule on costs. As stressed in Christoph H. Schreue, The ICSID Convention: A Commentary (International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes 2001), p 1239:

“If parties reach a settlement before an award is rendered they may, in accordance with Arbitration Rule 43(2), request the tribunal to embody the settlement in an award. If the tribunal accedes to the request, the award should contain a decision on costs either based on the settlement or in addition to it. But if the parties do not request an award (Arbitration Rule 43(1)) or if the tribunal declines to endorse the settlement in the form of an award, the discontinuance of the proceedings will simply be noted in an order. Such an order will not normally contain a decision on costs.”

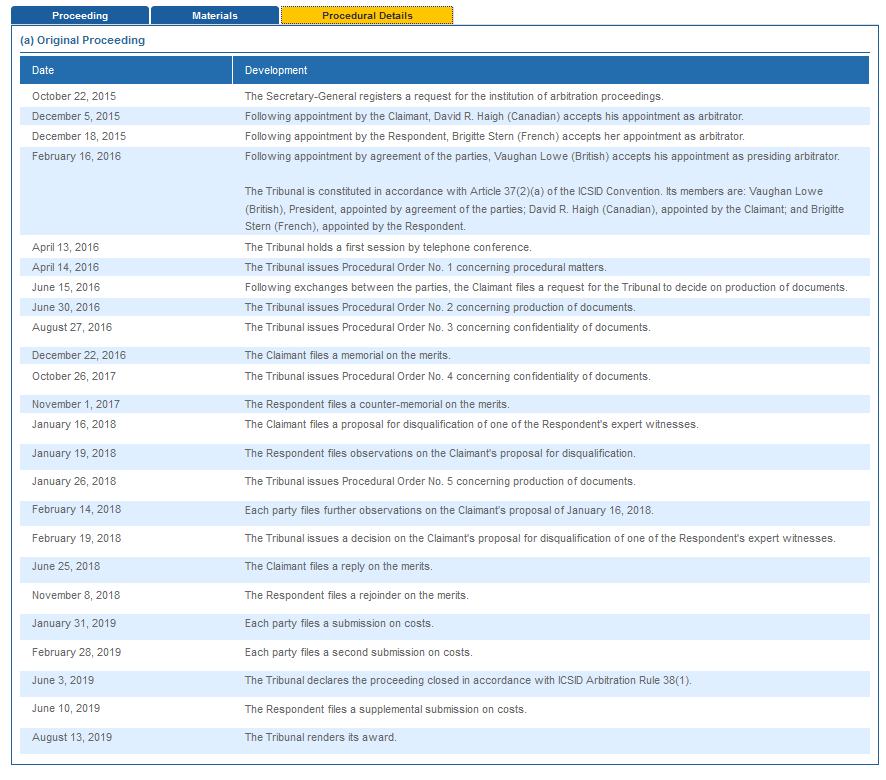

Considering the above legal background, let us take a look at the procedural history of SGRF v Bulgaria (Case No. ARB/15/43): Figure 2 below. There is no record of any Procedural Orders for discontinuance. It is also visible that there was no oral phase, which usually follows the written phase. The only logical conclusion is that parties settled and asked the tribunal to record their settlement as an Award pursuant to Article 43(2) and rule on costs. As seen from the procedural details, right after the written phase, the parties started making submissions on costs.

How to Settle? Why Settle?

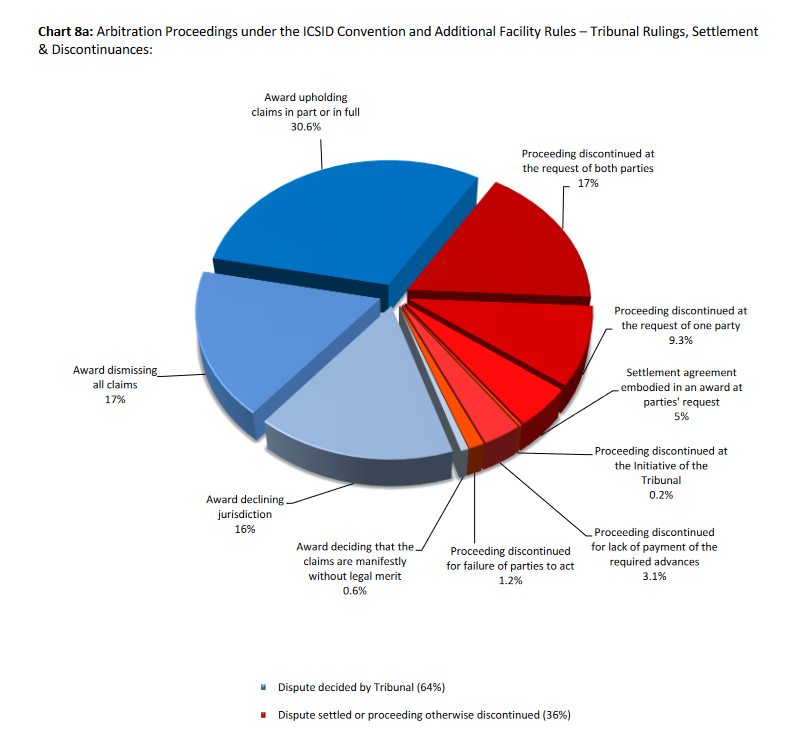

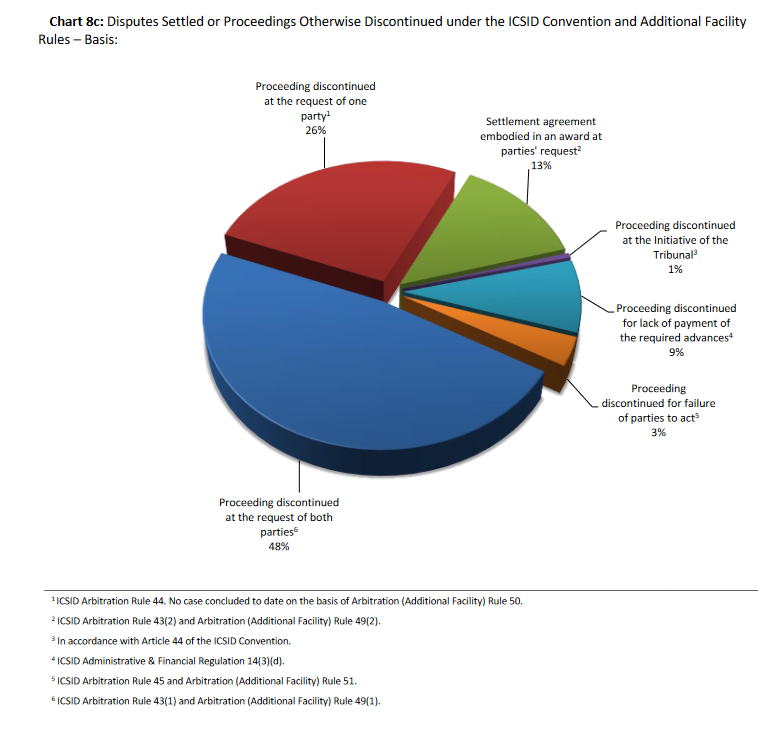

Invoking Rule 43 or Rule 44 of ICSID’s Arbitration Rules is a very common outcome. Let us take a look at official statistics by ICSID. Figure 3 shows the outcomes of all ICSID cases up to 2019 when THE ICSID CASELOAD—STATISTICS (ISSUE 2019-1) was published: 17% of proceedings were discontinued at the request of both parties, 9.3% of proceedings were discontinued at the request of one party, and in 5% of the cases the settlement agreement was embodied in an award at the parties’ request.

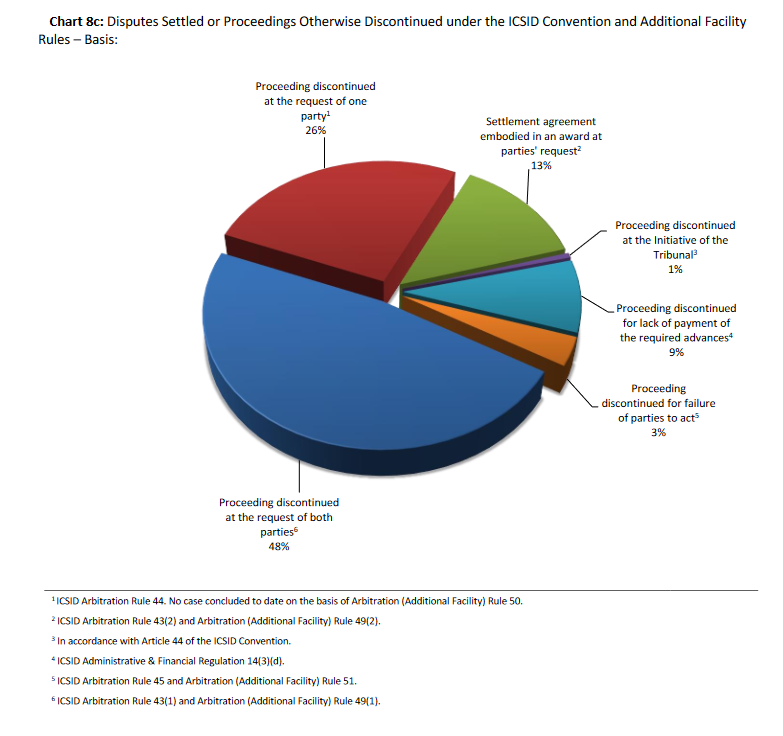

Figure 4 is even more interesting because it shows all reasons for discontinuance. In 13% of the cases, the settlement was embodied as an award at the parties’ request. In 26% of the cases, the proceedings were discontinued at the request of one party. In 48% of the cases, the proceedings were discontinued at the request of both parties.

Scholars have studied the motivation behind discontinuance of ICSID proceedings. Particularly interesting is this paper: Roberto Echandi and Priyanka Kher, ‘Can International Investor-State Disputes be Prevented? Empirical Evidence from Settlements in ICSID Arbitration’, ICSID Review, Vol. 29, No. 1 (2014), pp. 41–65.

The authors explain that often unilateral discontinuance under Rule 44 or discontinuance at the request of both parties pursuant to Rule 43(1) are the result of settlements. Simply, as part of the settlement, parties agree to discontinue proceedings.

However, there are claimants which prefer to embody their settlement as an Award pursuant to Rule 43(2) for enforcement reasons because their settlement will have the legal effect of an Award which is binding not only on the parties, but on all Contracting States to the ICSID Convention. See Articles 53 and 54 of the ICSID Convention itself:

Article 53

(1) The award shall be binding on the parties and shall not be subject to any appeal or to any other remedy except those provided for in this Convention. Each party shall abide by and comply with the terms of the award except to the extent that enforcement shall have been stayed pursuant to the relevant provisions of this Convention.

(2) For the purposes of this Section, "award" shall include any decision interpreting, revising or annulling such award pursuant to Articles 50, 51 or 52.

Article 54

(1) Each Contracting State shall recognize an award rendered pursuant to this Convention as binding and enforce the pecuniary obligations imposed by that award within its territories as if it were a final judgment of a court in that State. A Contracting State with a federal constitution may enforce such an award in or through its federal courts and may provide that such courts shall treat the award as if it were a final judgment of the courts of a constituent state.

(2) A party seeking recognition or enforcement in the territories of a Contracting State shall furnish to a competent court or other authority which such State shall have designated for this purpose a copy of the award certified by the Secretary-General. Each Contracting State shall notify the Secretary-General of the designation of the competent court or other authority for this purpose and of any subsequent change in such designation.

(3) Execution of the award shall be governed by the laws concerning the execution of judgments in force in the State in whose territories such execution is sought.

Finally, there could be many reasons why parties to a dispute may want to settle. Less today could be better than more tomorrow, especially if the respondent agrees to pay quicker or to include additional favors as part of the settlement deal. As explained in my previous article “An Arbitration Mystery and Bulgaria’s Rule of Law: How Arnold & Porter Gave Away the Existence of a Secret Deal, SGRF v Bulgaria is of paramount importance for Bulgaria’s government for it can expose the corrupt practices of the regime. When the tribunal records the settlement as an Award, it does not provide legal reasons, which is what the Bulgarian government wanted. Moreover, as explained in the next section, Bulgaria’s government relied on the fact that citizens do not have a background in ICSID arbitration to portray this outcome as a victory. But is this really so?

Government Propaganda, Paid Articles, and Unprofessional Journalism

In my prior article, I introduced you to the government propaganda in April 2019 when Bulgaria’s Ministry of Finance and the Bulgarian National Bank announced that SGRF withdrew its claim against Bulgaria. In this section, I provide an illustration of the propaganda which followed the rendering of the Award on 13 August 2019. The Ministry of Finance was so unsure that media would publish anything that they paid for publication. Figure 5 shows a paid article in Capital of 17 August 2019.

The title of the article is “The Arbitral Tribunal in Washington Decided Conclusively the Dispute between Bulgaria and the Omani Fund: SGRF Withdrew its Claims Without the Option to Litigate Again.” The last sentence of this announcement is even more peculiar:

“in accordance with that withdrawal, the tribunal finally dismissed the claims as unfounded and ordered the claimant to pay all costs”

One does not need a background in ICSID arbitration to see that something is fishy. If one withdraws a claim, the court/tribunal does not rule on the merits of a dispute. If one researches the Arbitration Rules of ICSID, as I have done and explained to you, this statement is even more problematic. The emphasis that the claim was withdrawn “without the option to litigate again” also gives away a settlement. If one discontinues proceedings pursuant to Rule 43(1) or Rule 44, one does not lose the right to litigate again.

A few hours after this paid article was published, other media tuned into the disinformation campaign. Dnevnik, Capital’s sister edition, published an article entitled “The Claim against Bulgaria Regarding Corporate Commercial Bank Has Been Conclusively Dismissed in Washington,” which is not marked as a paid publication this time. Any lawyer would agree that there is a huge difference between withdrawal of a claim for whatever reason and the tribunal dismissing all claims as unfounded. Dnevnik‘s assertions are even more problematic in light of our analysis of ICSID’s legal framework above.

The article published in Clubz is, frankly, absurd. The title is “The Omani Fund Lost the Arbitration Dispute Regarding Corpbank.” The subtitle is “The claim was withdrawn, the costs will be paid by Bulgaria.” Clearly, withdrawing a claim before a court/tribunal does not make you lose the case.

I have accumulated a collection of unprofessional articles on the matter as well as tweets by people like Betina Joteva, a public servant with no expertise in international arbitration, which clearly illustrate the scale of disinformation. One may reasonably suspect that this media hysteria was deliberately induced to deviate attention from what truly matters: what are the terms of this settlement?

What Next?

According to an article in the Global Arbitration Review of October 2015, the claimant asked for “the book value of [its] investment as per the day [Corpbank] was stopped as well as interest”. My guess, as a former damages aficionado, is that the claim was for more than 120 million Euro. Corpbank was subjected to a corporate raiding attack by state institutions, its license was withdrawn, and nobody was allowed to appeal the decision by Bulgaria’s central bank. SGRF held nearly 30% of the bank’s shares. Surely, considering the size of investment and the circumstances, settlement between them and Bulgaria was not easy to achieve.

Pursuant to Rule 48(4) of ICSID’s Arbitration Rules, ICSID publishes the full text of awards only if parties consent to this:

Rule 48

Rendering of the Award

...

(4) The Centre shall not publish the award without the consent of the parties. The Centre shall, however, promptly include in its publications excerpts of the legal reasoning of the Tribunal.

As stipulated by the same rule, ICSID shall publish excerpts promptly. “Promptly” seems to be a flexible term since some ICSID cases which were decided in 2015, such as Novera v Bulgaria, remain a mystery. The best way forward is to force Bulgaria’s government to disclose the full text of the Award, which ICSID does not mind. If interested in ICSID’s policy on transparency and publication, take a look at this fascinating read: Alberto Malatesta and Rinaldo Sali, The Rise of Transparency in International Arbitration. Those with forensic skills and/or an interest in finance may be tempted to track the payment which will be made or has been made.

Overall, the intentional manipulations by Bulgaria’s government serve as one more example of the lack of rule of law in Bulgaria. The litigation regarding Corpbank continues in other venues, so sooner or later the truth about the government’s plan to force Corpbank (the forth largest lender) into artificial bankruptcy, so that its assets could go into the hands of straw men of politicians, will come out.

UPDATE: This article was published on 21 August 2019. As I have received some questions about costs, here are further clarifications:

When parties ask the arbitral tribunal to embody their settlement in an Award and rule on costs, the tribunal only rules on the costs which have not been settled between the parties. In ICSID arbitration proceedings, there are three types of expenses: 1) expenses incurred in connection with the proceedings (legal representation, costs of witnesses and experts, etc.); 2) fees/expenses of the arbitral tribunal; 3) fees for using ICSID’s facilities.

It should be noted that ICSID case law indicates that ICSID tribunals do not endorse the so-called “winner takes all approach”. Even if hypothetically there is an Award which upholds all claims, the tribunal will often aim at some form of apportionment of costs. In the case of SGRF v Bulgaria, since the government claims the tribunal ruled that SGRF would pay for the expenses, one has to ask – which expenses? If, in their settlement, parties have agreed that legal representation would be paid by Bulgaria, it may be the case that the tribunal ruled that SGRF would pay for the rest.

UPDATE 2: I have just learned that Defakto, a Bulgarian site specialized in legal news, has translated my article in Bulgarian. You can see it here. I would like to thank them for covering my article and translating it because it can reach more people in Bulgaria! I want to inform my readers that I am not responsible for the translation and I have not been asked to approve it.

UPDATE 3: Based on best practice, ICSID will ask Bulgaria and SGRF if they want to make their Award public within 2 months (usually 2 months after the Award has been rendered). Bulgaria’s government will surely refuse. One may suspect there are confidentiality agreements as part of the settlement package (either in the Award or in side contracts). Overall, this does not benefit Bulgaria in any way: it just benefits the corrupt regime.

UPDATE 4: Banker, a Bulgarian media specialized in banking news, has also published a resume of my article in Bulgarian. Thank you for covering my article!

If you are interested in daily updates on Bulgaria’s declining rule of law, you can follow me on Twitter @radosveta_vass

If concerned about the deplorable state of Bulgaria’s rule of law, consider reading:

- An Arbitration Mystery and Bulgaria’s Rule of Law: How Arnold & Porter Gave Away the Existence of a Secret Deal

- All You Need to Know About Bulgaria’s Rule of Law in 10 Charts

- 8 Worrisome Charts on the Grim State of Bulgaria’s Rule of Law

- Paradoxes of Bulgaria’s Rule of Law

- Is Bulgaria’s Rule of Law about to Die under the European Commission’s Nose? The Highest-Ranking Judge in the Country Fears So

- Criminal Corporate Raiding in Bulgaria

10 thoughts on “Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire! How Bulgaria Deliberately Misinformed the General Public about the Outcome in ICSID Case No. ARB/15/43 (SGRF v Bulgaria)”

Comments are closed